An inexplicable athlete and tennis' irresistible force paradox

Connor Joyce • June 20th, 2025 1:02 pm

I had one thing written on this page before the first Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner grand slam final: What happens when an unstoppable object meets an immovable force?

The better question in hindsight: what doesn’t happen?

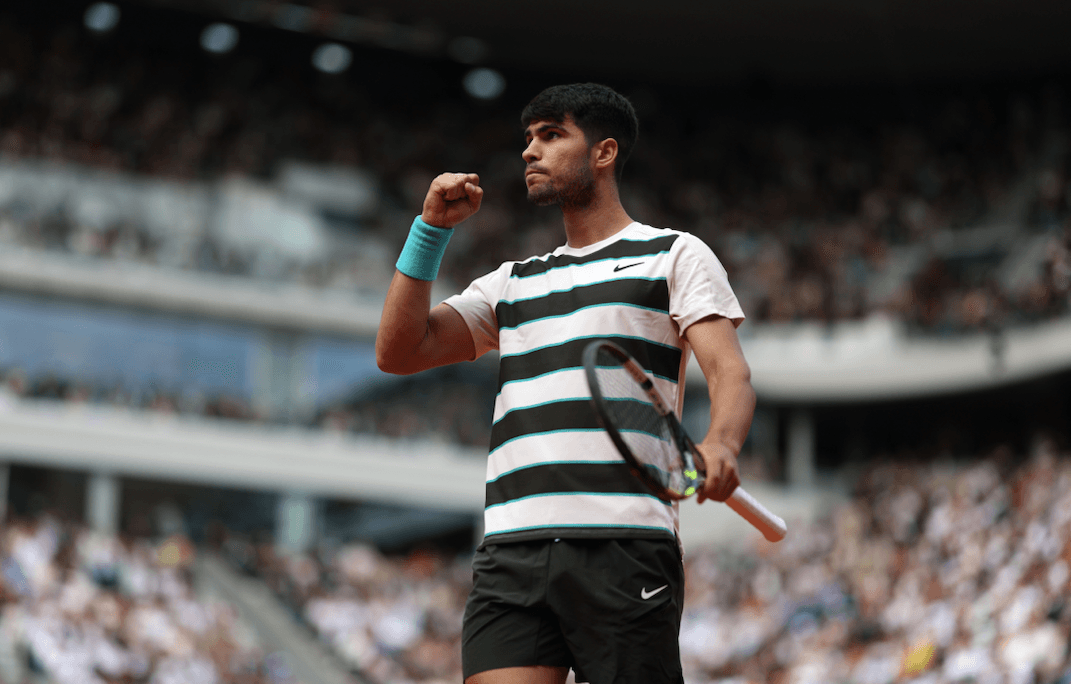

Tennis’ equivalent of the irresistible force paradox. The first major final between a 22-year-old Spaniard and a 23-year-old Italian, the two best tennis players on the planet. They’d won five majors in a row, seven of the last 10, and neither had lost a Grand Slam final (combined 7-0 record).

Two athletes unfazed by the biggest stage. Two young men who, to quote Sinner, ‘like to dance in a pressure storm’. And two tennis players in impeccable form.

Sinner holds 20 straight Slam wins and an unblemished set record for the tournament. Alcaraz is holding 13 consecutive Roland Garros wins and four straight victories in the head-to-head. The world No.1 vs the world No.2 in a genuine coin flip. You’d almost tip the draw.

But tennis doesn’t do the draw, and on Sunday in Paris, one man had to lose.

A full-house Chatrier crowd was brimming with anticipation. Cloudy afternoon. Roof open.

Ready, play.

The first game of the match set the tone, one that would reverberate for the next five and a half hours. Alcaraz came out aggressive, attacking returns, creating break points, and forcing Sinner to keep pace, which he did, with a twelve-minute service hold. It was like a friendly heads-up to the Chatrier crowd – and to lounge rooms around the world – to settle the hell in.

At 2-2, Alcaraz landed the first blow in the final, a deserved break of serve. In the moment, it felt like a sizable jab; in hindsight, a mere scrape to the leg. Sinner would hit straight back and eventually steal a chaotic opening stanza: the most straightforward set of the match.

Alcaraz is no stranger to dropping sets, particularly at the 'slams'. For him, it’s never a cause for concern.

Following a come-from-behind victory over Lorenzo Musetti in the semi-final, Alcaraz revealed that when he does drop sets, he tells himself, “I lost the set", not "he won the set.”

And he’s right. This fluctuating, inexplicable, unbelievable tennis player always has matches on his racquet. His peak level is the peak level in the current men’s game.

His greatest rival, Sinner, is diametrically relentless, operating more like a machine calibrated to near-perfection. His top gear is one rung below, marked by a gap so thin even he couldn’t pierce a backhand down the line through it.

But he holds that level for longer, and it renders the prospect of winning three straight sets against him a near impossibility. It explains his unbroken 59-match streak without such an occurrence.

Alas, the second stanza felt significant. And the less urgent Sinner jumped to a 3-0 advantage. Then 4-1. Then 5-2 and closing in on a two-set lead.

Serving at 2-5, Alcaraz got his first hold to ‘fifteen’ for the match. Finally, a chance to breathe before preparing to return. And importantly, some momentum to break, which he used. The first counterpunch from Alcaraz. He put his ear to the crowd (the first of many). This final was alive.

It felt like a turning point. Short-term, it wasn’t. In the long run, it may have been. For now, it set up a crucial second-set tiebreak.

On serve at 2-3 in tennis’ shootout, Sinner ended a ten-shot exchange by freezing Alcaraz with a forehand winner to snatch the mini break. It was the moment of the match so far, paving his way to a two-set advantage.

Even for Carlos Alcaraz's standards, he was truly on the ropes. Sinner had won eleven consecutive sets in grand slam finals – a feat only matched by Pete Sampras – and thirty-nine straight matches from two sets up at majors. Alcaraz, meanwhile, had never come back from two sets to love down in eight previous attempts.

But for those who’d been captivated by this Murcia-born prodigy, from his 16-year-old heroics in Rio de Janeiro to his ‘dethroning’ of Novak Djokovic at Wimbledon, a comeback didn’t feel out of reach. It almost felt destined. For Alcaraz, a grand slam final seemed like the perfect stage to do something he’d never done before.

In every press conference throughout the tournament, the Spaniard spoke about the nature of Grand Slam matches; the luxury of best-of-five. “You have more time, you have more sets, just to get back if you lose your focus a bit.”

Everyone knows that. But Alcaraz plays like a man fully aware of it. He truly enjoys it. I’ve only seen one other person compete with such an assuredness at times, and he’s won 24 of these things.

With all due respect, this wasn’t Damir Dzumhur or Fabian Marozsán on the other side of the net. This was the world’s best player, at the peak of his powers, and Alcaraz was flirting with danger.

Along came the third set. The Spaniard needed a strong start. He got the opposite. Broken immediately, he was backed deep into a corner: down two sets, 1-0, 30-0.

After nearly two-and-a-half hours, he was still at least seventy-two points from victory, practically the farthest one can be in a tennis match.

Andy Roddick calls best-of-five-set tennis the ultimate test of physical and mental resilience because there are no shortcuts. When coming back from two sets down, "you can't skip steps”. Unlike many sports, where you can turn a scoreline in a matter of minutes, grand slam tennis requires hours. It has to be incremental. 30 seconds at a time. Point. By. Point.

In that moment, Alcaraz rose from the canvas, right when he needed to.

His first real jab? A forehand drive volley winner at 30-15, with Sinner trying to consolidate the break. The drive volley: tennis’ unsung adrenaline shot. Rarely in the spotlight, but so often the spark that shifts momentum.

The defending champion broke back, held comfortably, and then broke again to lead 3-1. Still down two sets, Alcaraz pointed to his ear again, and Chatrier answered. A second call, in a match where he’d been almost entirely behind. Not out of arrogance, more like a rockstar inviting the chorus.

I’ve long thought the best tennis players are like rock stars. Two athletes – often one much more than the other – selling out arenas across continents. It’s rare in sport. Magic Johnson accurately described a true sporting superstar as someone who ‘can go on the road and sell the building out.’ Alcaraz and Sinner? They already can, all over the planet. At 22 and 23, they’ve battled in packed arenas from New York to London, Beijing to Paris, and they’ll each sell out many more before it’s all said and done.

Alcaraz took the third 6-4, but not without drama. He was broken serving for it, only to change ends and break back to love. Suddenly, the momentum felt firmly back in Spanish hands. Two sets to one down, right where he wants Jannik Sinner.

But Sinner was not going away. Desperate to avoid a fifth set, he stayed firmly in control. A string of service holds started the fourth, Sinner’s much more comfortable than Alcaraz’s. Yet, the Spaniard found himself up 3-2.

When you watch a match like this one, it’s impossible to remember everything. Certain points stick with you, usually the biggest ones. But the next twenty minutes – the most important stretch of Alcaraz’s career and one of the most astounding in tennis history – are quite a blur to me. ‘Carlitos’ later admitted a similar feeling.

In a flash, Alcaraz went from leading the fourth set to down three championship points: a deficit no player in tennis history had ever overcome. It was the moment, one instantly etched in tennis folklore. That scoreboard photo, paired with the words ‘Carlos Alcaraz won this tennis match’.

Love-forty.

The air went out of Philippe Chatrier.

Journalists scrambled to meet article deadlines.

TV presenters hurried to finish their makeup.

Photographers positioned themselves for their moment.

Uber demand rose outside the grounds.

My ‘Sinner-champion’ graphic was all ready to go (will forever remain in the drafts).

Every second fan had their phone out to capture the moment Jannik Sinner won Roland Garros.

I’ve since reflected on why it felt over, because in that moment, it absolutely did.

This remarkable athlete, Carlos Alcaraz, had given us every reason to believe his matches weren’t complete until the handshake. He won his first grand slam title from match point down (against Sinner in the quarters). He won his first Wimbledon final over seven-time champion Djokovic, from the edge of defeat. He won his first Roland Garros title from two sets to one down in the semifinals and the final.

But this was different. Not only down three championship points, but against the world No.1 in a flow state. As Alcaraz put it, Sinner “couldn't miss any ball”. From 2-3 down, he’d held to love, broke to love, held to fifteen, and was on the brink of another love break.

He’d won 15 of the last 16 points and needed just one of the next three to lift the title. That’s why the buzz went out of Chatrier. Sinner had all but unplugged the rock concert mid-song.

Even coach Juan Carlos Ferrero, who’s seen it all with Alcaraz, admitted he didn’t believe in that moment. But one man kept the faith: possibly the only person in Chatrier who hadn’t accepted defeat. “At 0-40, [Carlos] looked at me and still (shook) the racquet, like saying, I'm still here, saying vamos,” Ferrero said of his student. Who on Earth does that, seriously?

Championship point, un.

The first was the most intense, though it didn’t feel it. A seven-shot exchange, with Alcaraz’s fifth strike, a forehand, landing just inches inside the baseline. So close, Sinner’s mind would have wandered into celebration. He’d then slap a forehand inches long himself.

Tennis’ scoring system is a masterpiece. There’s no clock to drain, no lead you can protect; just a dynamic finish line reserved for the winner of the final exchange. At that moment, Sinner was one point from it. Alcaraz was still a minimum of forty. In hindsight, both men were more than 120 points from a warm embrace.

Championship point, deux.

The fun part about serving down match point is it’s on your racquet. The terrifying part: it’s on your racquet.

Sinner got one look at a second serve. Alcaraz, unlike his opponent, does occasionally throw in a double fault – seven in the match, to Sinner’s zero. But not here. He went safe: 144km/h up the middle, asking to be hit. Sinner rightly pounced on it. A backhand return he’d make nine times out of ten. One that comes back two times out of ten. This one missed long.

Four nights after the final, I couldn’t fall asleep thinking about that miss. I’m sure it hasn’t been on Sinner’s mind.

Championship point, tres.

The final chance, for at least a minute. A better Sinner return. Another deep Alcaraz forehand, and another Sinner error. Forced but uncharacteristic, at least for a cyborg (as Roddick described him).

Three saved, but still under pressure. Point by point.

Then came a timely ace. Then a ridiculous forehand down-the-line winner to hold. The great escape.

Alcaraz paused, stared, bumped his fist, pointed to his ear again, and summoned every man, woman, and child in Chatrier to rise as one. Sinner was about to serve for the Roland Garros title.

I’ve never seen anything like it. Alcaraz made everyone in the stadium – probably including Jannik Sinner – forget that he still had to break. And break the guy who holds serve over 91% of the time, more effectively than anyone else on tour in 2024 or 2025.

He couldn’t not break. And he did, to fifteen. 5-5 in the fourth.

There’s a Spanish word, 'alegría'. While I was in Madrid, a journalist told me it’s like their way of life in Spain: living joyfully and spiritedly. I saw it during the nationwide power outage when the community came together, singing in the streets. I saw it just as strongly from one man in the fourth set on Chatrier.

In the weeks leading into Roland Garros, Alcaraz was asked what the key to his game is. His forehand? His movement? “The most important thing is to play with joy,” he said. It might just be true. Even with everything on the line, it’s still when he’s at his best.

Another tiebreak: this time to stay in the match. To force a fifth set, to migrate into his natural habitat.

Another tiebreak: this time to stay in the match. To force a fifth set, to migrate into his natural habitat.

Sinner got the early mini break for 2-0. It didn’t matter. Alcaraz reeled off seven of the next eight points. Just like the Beijing final, his top level. On we go.

Roland Garros 2025 began with the celebration of one Spanish legend. It now felt inevitable that it would end with the coronation of an emerging one.

Sinner had never won a match over four hours. He’d need well over five to win this one and had already shown signs of cramp and fatigue.

For a year now, endurance had been the only question hanging over him. Winless in his six longest matches. 1-5 in his past six five-setters.

But it’s a test he rarely faces. He’s so good, he doesn’t need five sets to beat anyone else.

His US Open final last year? Straight sets.

His Australian Open final this year? Straight sets.

His semifinal two days prior against Djokovic? Straight sets.

But his last two Grand Slam matches against Alcaraz? Five set defeats.

And this one, despite being level, felt impossible to claw back.

I told my colleague, ‘If Alcaraz wins this 6-0, it’s still the most incredible match I’ve seen live’. We’d witnessed everything already. The world No.1 and No.2 battling for five hours in a major final, with a two-set comeback and match points saved. Anything more was a bonus.

Almost immediately, it entered the conversation as one of the all-time great tennis matches. In the days since, I’ve seen some question the quality compared to past finals, referencing the 137-unforced error count. Sure, there were many throughout, but 137 exchanges between the world’s two best players on the world’s toughest surface, ended ‘unforced’? Please.

Two elite movers, sublime returners, exceptional defenders. A matchup where the winner count isn’t exaggerated by aces – just 15 from 385 points. And one where points that would have ended with a winner five shots earlier against anyone else, end with an ‘unforced’ error instead.

Undoubtedly, there were dips from both players during the first four sets. They only added to the drama. But not in the decider. The fifth could be the best set of tennis I’ve ever seen.

Alcaraz broke right out of the gate and quickly led 2-0. I glanced towards my colleague, with nothing but a ‘here we go’ type smirk. The bagel looked plausible. I’d forgotten Sinner’s the one handing out bagels in men’s tennis, not receiving them.

The Italian fought back, almost breaking at 2-1. Still, given Alcaraz’s level, Sinner found himself serving down 3-5. He held, and more than an hour later, it was Alcaraz’s turn to serve for the title.

If you still haven’t watched this match or any highlights, firstly, sorry. Secondly, just track down the final sequence from 5-4 in the fifth. Trust me, you won’t be disappointed.

If you still haven’t watched this match or any highlights, firstly, sorry. Secondly, just track down the final sequence from 5-4 in the fifth. Trust me, you won’t be disappointed.

Alcaraz’s variety had been effective all set long. The drop shot was working supremely against Sinner’s fatigue. Down 15-30, serving for the title, he turned to it again, hitting one he thought was so good he didn’t even chase it in.

Unbelievably, Sinner retrieved it and deftly executed a counter drop shot winner, one that drew a collective gasp from a speechless Chatrier. I spent the next twenty-odd seconds in a state of shock, blankly staring around the press box as if someone could explain how he made that ball. A few days on, I still don’t know.

Sinner broke, and then held from deuce with more incredible shot making. Suddenly, he was one game away, again.

For me, this turnaround was just as mind-blowing as Alcaraz’s in the fourth set. I cannot overstate how extraordinary it would have been if Sinner had reeled off four straight games, from 3-5 down in the fifth, after five hours, against tennis’ most durable athlete. And he almost pulled it off.

Cometh the 5-6 game. In almost any other tennis match, this would be the defining moment. Here, it could almost get lost amongst the drama. Alcaraz himself said this game was the most memorable for him, more so than his ‘Houdini’ act in the fourth.

The intensity of both men was noticeably higher than it had been all afternoon. Sinner was pressing, and Alcaraz found himself down 15-30, staring down the barrel of two more championship points.

He got to 30-30, then played a point which basically said, ‘I’m not losing this tennis match’. Sinner lashed a perfect crosscourt forehand return, one that would have ended the point – or at least set up a winner – against anyone else. Championship point, quatre.

Somehow, Alcaraz dug out a squash-like slice that landed in the opposite corner of court Phillipe Chatrier and set up a backhand winner. As quickly as one will ever go from desperate defence to lethal offence. And to avoid going down match point, no less.

We reached deuce, at 5-6 in the fifth: now the longest Alcaraz-Sinner match to date, only just eclipsing their five-hour-15-minute US Open quarterfinal (2022).

What followed were ten minutes of peak Carlos Alcaraz. He reached that rung, a part of the ladder that very few in tennis have ever gotten to. A level so high it could take a little heat off John McEnroe for suggesting he’d beat prime Nadal here.

It’s a sequence that words can’t do justice to, but three moments stood out.

It’s a sequence that words can’t do justice to, but three moments stood out.

The backhand pass to force the tiebreak. Absurd. The lunging forehand drive volley at 3-0. Laughable. And the angle-shifting backhand down the line at 6-0. The absolute dagger.

From 5-6 deuce, Alcaraz won NINE straight points to lead the tiebreak 7-0. It was the first time in the entire tournament that he won nine consecutive points. In fact, it was the first time he’d done so since February: a 30-match stretch.

You just could not manufacture a better statistic to encapsulate everything that is Carlos Alcaraz Garfia.

And then at 9-2, after everything, he finished it in the most fitting way possible: a running forehand passing winner. I’m chuckling as I write. It’s the ending any screenwriter would have scripted, and yet it arrived organically, capped by a collapse onto the clay.

What more is there to say?

What more is there to say?

In open-era Grand Slams, it was:

The second-longest men’s final ever.

The third men’s final won from match point down.

The third men’s final to finish in a fifth-set tiebreak.

The ninth men’s final won from two sets to love down.

193 points to 192. A five-and-a-half-hour rollercoaster: the kind only tennis can provide.

Sinner played his heart out and did not deserve to lose.

Alcaraz stared down 'task impossible' and conquered it.

To win his fifth major title at the exact same age, to the day, as his idol, Rafael Nadal. On the court where they’d just immortalised Rafa’s footprint. And under Roland Garros’ iconic tagline, never more fitting: ‘Victory Belongs to the Most Tenacious’.

So, what happens when an unstoppable object meets an immovable force?

In physics? Who cares. In Paris? One of the greatest tennis matches ever played.